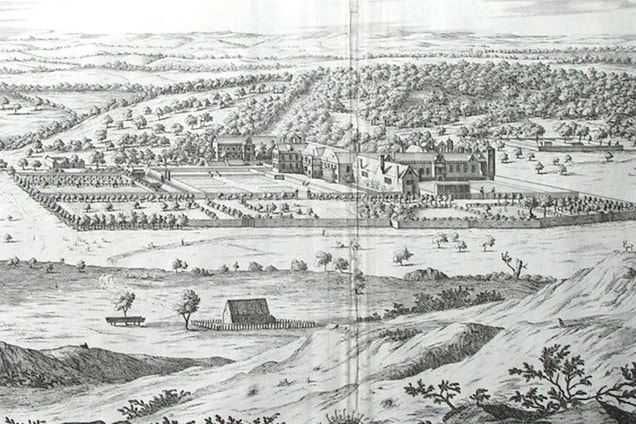

Mid-July 1642 saw King Charles the First arrive at Leicester on a campaign to raise support for his quarrel with Parliament. The King's presence in the county spurred the area's leading Royalist, Lord Henry Hastings, to attempt to seize arms and ammunition held at the Earl of Stamford's house at Bradgate. Stamford (Lord Grey's father) had already raised a body of men to guard the house, equipped with weapons taken from Leicester's county magazine [1].

Commissioned to raise troops for the King's cause, Hastings "loudly proclaimed his intention to seize the town magazine by force from Bradgate, if he could not obtain it by fair means . . . attended by a large following, he rode up to the front door of Bradgate Hall and held a stormy interview with the Earl, in which he demanded in the King's name the surrender of the magazine; but Stamford, safely protected behind the defences, and guarded by his musketeers, declined." [2] Rebuffed, Hastings withdrew.

Commissioned to raise troops for the King's cause, Hastings "loudly proclaimed his intention to seize the town magazine by force from Bradgate, if he could not obtain it by fair means . . . attended by a large following, he rode up to the front door of Bradgate Hall and held a stormy interview with the Earl, in which he demanded in the King's name the surrender of the magazine; but Stamford, safely protected behind the defences, and guarded by his musketeers, declined." [2] Rebuffed, Hastings withdrew.

Henry Hastings was the second son of the Earl of Huntingdon, and scion of a long-established Leicestershire land-owning family. A more direct rival to Lord Grey would be hard to imagine: both were the sons of local aristocracy; Hastings would appointed Colonel-General of Royalist forces in the north-Midlands, just three months after Lord Grey had been made Parliament's Lieutenant-General for the same region. In the forthcoming Civil War, the two rival families would divide Leicestershire between them, while the two sons, Hastings and Grey, "fought the public quarrel with their private spirit and indignation" [3].

Rupert's Raid

In August 1642, four days after Charles I had formally declared his intention to wage war on Parliament, Hastings reportedly returned to Bradgate accompanied by Prince Rupert and his horsemen. Both Stamford and Lord Grey had by this time marched to join the Earl of Essex's army in the south of the country.

The Royalist's raid on Bradgate was reported by a Parliamentarian newspaper in London:

The Royalist's raid on Bradgate was reported by a Parliamentarian newspaper in London:

Upon 26th August Prince Rupert together with Master Hastings and many cavaliers, went to my Lord Grey, the Earl of Stamford's house, from whence they took all arms, and took away and spoiled all his goods, and also the clothes of his chaplain who was fain to flee for his life: And some chief ones asked, "Where are the brats, the young children?" Swearing, "God damn them! They would kill them, that there might be no more of the breed of them.'' [4]

It is difficult to establish the truth of any event from just one historical source. However, it is quite plausible that a second attempt to seize the magazine at Bradgate was more successful, given the absence of Stamford and his soldiers. The extent of any damage caused is unclear, but certainly none of Stamford's younger children (if present) were harmed.

Incidentally, Prince Rupert was not the first Royal to have visited Bradgate: King Charles had been a guest of Stamford in the early 1630s, when the earl had been better disposed towards Royalism and had hoped to obtain favour by accommodating the monarch during his tour of the country.

Incidentally, Prince Rupert was not the first Royal to have visited Bradgate: King Charles had been a guest of Stamford in the early 1630s, when the earl had been better disposed towards Royalism and had hoped to obtain favour by accommodating the monarch during his tour of the country.

Following the first Civil War, Lord Grey was able to purchase Coome Abbey near Coventry, the sequestered property of Royalist Lord Craven. Grey favoured Coome Abbey as his residence through the 1650s, although Bradgate was still inhabited: the fugitive Royalist, Edward Massey (formerly Grey's second-in-command), fled to Bradgate following the battle of Worcester, and there gave himself up to the mercy of Anne Cecil, Grey's mother, who reportedly tended to his wounds.

After 1660 Bradgate became the main family residence once more when Coome Abbey was returned to its pre-war owner. Following the death of Lord Grey's son, Thomas, in 1720, the Stamford title passed to cousins, who lived at their own seat at Enville in Staffordshire. Bradgate’s role was reduced to little more than a hunting lodge, and the buildings began their slow descent into the ruins they are today.

References:

1 Poynton, C. H., Romance of Ashby-de-la-Zouch Castle (Birmingham: 1902), p. 176

2 ibid., p. 177

3 Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion, v, p.417

4 Remarkable Passages from Leicester (London: 1642), quoted in: Richards, J. Aristocrat and Regicide, The Life and Times of Lord Grey of Groby (London: 2000)

Source: J. Richards, 'The Greys of Bradgate in the English Civil War: a study of Henry Grey, first Earl of Stamford, and his son and heir Thomas, Lord Grey of Groby', Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, vol.62, 1988, pp.32-52

Robert Hodkinson, September 2015 (rev. 2018)

1 Poynton, C. H., Romance of Ashby-de-la-Zouch Castle (Birmingham: 1902), p. 176

2 ibid., p. 177

3 Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion, v, p.417

4 Remarkable Passages from Leicester (London: 1642), quoted in: Richards, J. Aristocrat and Regicide, The Life and Times of Lord Grey of Groby (London: 2000)

Source: J. Richards, 'The Greys of Bradgate in the English Civil War: a study of Henry Grey, first Earl of Stamford, and his son and heir Thomas, Lord Grey of Groby', Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, vol.62, 1988, pp.32-52

Robert Hodkinson, September 2015 (rev. 2018)