Who put the 'Ex-' in Xmas?

Parliament's distaste for festive merry-making in the 1640s was less to do with puritanical religious views than with political expedient. The key to understanding the Long Parliament's aversion to Christmas celebrations can be found in two pivotal dates that, seemingly, have nothing to do with the Civil War: 1583 and 1958.

Happily, the idea that Oliver Cromwell outlawed mince pies in a fit of mirthless tyranny can now be consigned to the dustbin of history. Even the most cursory glance at the evidence shows it to be a myth, and The Law Commission has done a good job to highlight the lack of proof for Cromwell's confiscation of festive food.

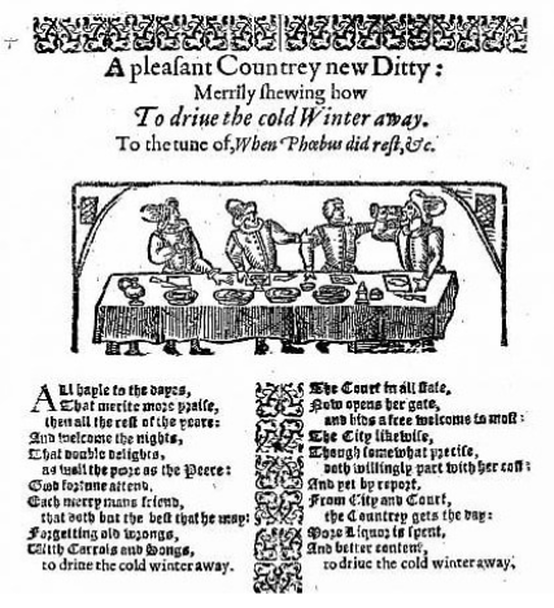

However, in the hundred years between the English Reformation and the Civil War, the religious observance of Christmas had come under increasing attack from those who wanted the English church to distance itself from traditional Medieval feast days - the so-called 'Puritans'. Elizabethan moralist Philip Stubbs had complained that “more mischief is at this time committed than in all the year besides . . . to the great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm” (Pilmot, 1960). In 1632 the author and lawyer William Prynne argued that if the Muslim “Turks and Infidels” could see how the English celebrated the birth of Christ, they could be forgiven for thinking that Jesus was venerated as “a glutton, an epicure, a wine-bibber” (ibid). Dorothy Hazzard, a leading voice among the Bristol baptist congregation, forbade herself both merriment and the religious observation of the nativity: she would open up her late husband's grocery shop on the morning of 25 December and brazenly sit sewing “on the time they called Christmas day” (Hayden, 2004).

However, in the hundred years between the English Reformation and the Civil War, the religious observance of Christmas had come under increasing attack from those who wanted the English church to distance itself from traditional Medieval feast days - the so-called 'Puritans'. Elizabethan moralist Philip Stubbs had complained that “more mischief is at this time committed than in all the year besides . . . to the great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm” (Pilmot, 1960). In 1632 the author and lawyer William Prynne argued that if the Muslim “Turks and Infidels” could see how the English celebrated the birth of Christ, they could be forgiven for thinking that Jesus was venerated as “a glutton, an epicure, a wine-bibber” (ibid). Dorothy Hazzard, a leading voice among the Bristol baptist congregation, forbade herself both merriment and the religious observation of the nativity: she would open up her late husband's grocery shop on the morning of 25 December and brazenly sit sewing “on the time they called Christmas day” (Hayden, 2004).

Yet this lengthy puritanical assault on had little impact on how the majority of people celebrated Christmas. Ronald Hutton notes that virtually all the church accounts for town and city parishes from the period record payments for holly and other evergreens with which churches continued to be decorated in the traditional manner. When in 1634 the rector of a Herefordshire parish was suspended by church authorities for his puritanical leanings it was noted that, despite his radical views, he still observed Christmas as a feast day (Bruce, 1864). Even an ardent parliamentarian such as Lord Brooke - who condemned episcopacy and died fighting in the Civil War - paid for musicians to entertain his household and guests over Christmas (Hutton, 1994). The only concession to puritanism when the church calendar of feast-days was reformed was to rename Christmas “Christ-Tide”, with the intent of removing the spectre of the Catholic 'mass' from the name of the traditional festival (ibid). For the best part of eighty years, then, the authorities had all but ignored the Puritans' aversion to the festive season. But in the 1640s this would change dramatically.

The Fasting Problem

Following the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion in October 1641, Parliament advocated that a national fast should be observed on the last Wednesday of every month, a day of humility during which the King's subjects would abstain from eating meat and prayers could be offered at church services for the defeat of the rebels. The King himself issued a proclamation for the monthly fast in January 1642. The decree was unpopular and its enforcement far from easy, evidenced by repeated parliamentary ordinances between August 1642 and December 1646 “to observe the Monthly Fast” (Commons Journal, vol. 3, passim). Acceptance may have been more widespread if those in authority had led by example: in December 1643 the conduct of several MPs was referred to a parliamentary enquiry after it was reported that certain members had been witnessed “dining and being in a Tavern, most of the Part of the Time that the House was solemnizing the Fast” (ibid, 353). But it was in 1644 that enforcing the monthly fast proved most problematic, because in December that year the fast-day fell on the 25th. The time had come for a political decision to be made about Christmas: either allow the traditional observation of Christmas to continue, or enforce the fast.

The most important thing to remember when discussing the Long Parliament's view of Christmas is that the 17th century Christmas was very different to that which we enjoy today. Christmas Day in Stuart England was not a time for partying, it was a religious observance. In 1612, the royal court observed 25 December as an official day of mourning for Henry, Prince of Wales, who had died the previous month. Samuel Pepys recorded his Christmases during the 1660s in his diary, and his day typically involved a church visit to hear a Christmas sermon followed by a formal dinner at home with few, if any, guests. Traditional Christmas festivities - exchanging presents, playing games, eating traditional foods - were in the 17th century confined to Twelfth Night, the last day of the Christmas season. Pepys described such Twelfth Night celebrations in 1669:

In the evening I did bring out my cake - a noble cake - and there cut it into pieces, with wine and good drink . . . did out so many titles into a hat, and so drew lots; I was the Queene; and Tho. Turner, King; Creed, Sir Martin Marr-all; and Betty, Mrs Millicent; and so we were mighty merry till it was night.

The shift of this kind merry-making from Twelfth Night to Christmas Day was done by the Victorians, and the Christmas that we celebrate today is largely a Victorian invention. So Parliament's decision in 1644 to forgo the reading of the Christmas Day sermon in churches, in favour of the observation of the fast, was perhaps not as joyless as we might presume. In fact, the decision to discourage Christmas celebrations was not religious but political, and the reasons why lay north of the border.

The most important thing to remember when discussing the Long Parliament's view of Christmas is that the 17th century Christmas was very different to that which we enjoy today. Christmas Day in Stuart England was not a time for partying, it was a religious observance. In 1612, the royal court observed 25 December as an official day of mourning for Henry, Prince of Wales, who had died the previous month. Samuel Pepys recorded his Christmases during the 1660s in his diary, and his day typically involved a church visit to hear a Christmas sermon followed by a formal dinner at home with few, if any, guests. Traditional Christmas festivities - exchanging presents, playing games, eating traditional foods - were in the 17th century confined to Twelfth Night, the last day of the Christmas season. Pepys described such Twelfth Night celebrations in 1669:

In the evening I did bring out my cake - a noble cake - and there cut it into pieces, with wine and good drink . . . did out so many titles into a hat, and so drew lots; I was the Queene; and Tho. Turner, King; Creed, Sir Martin Marr-all; and Betty, Mrs Millicent; and so we were mighty merry till it was night.

The shift of this kind merry-making from Twelfth Night to Christmas Day was done by the Victorians, and the Christmas that we celebrate today is largely a Victorian invention. So Parliament's decision in 1644 to forgo the reading of the Christmas Day sermon in churches, in favour of the observation of the fast, was perhaps not as joyless as we might presume. In fact, the decision to discourage Christmas celebrations was not religious but political, and the reasons why lay north of the border.

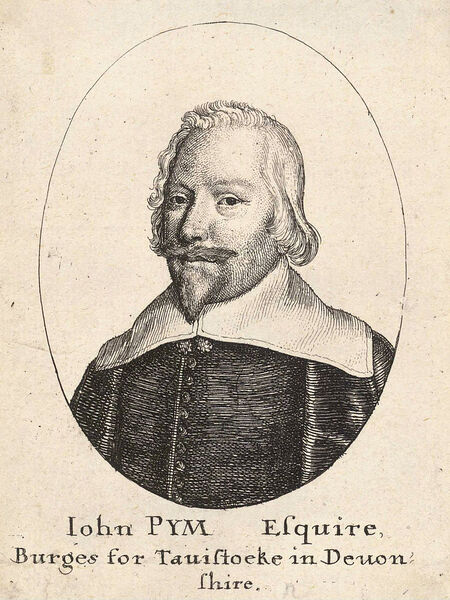

Pym and "The War Party"

By 1640 John Pym M.P. was de facto leader of the opposition to King Charles's government in the House of Commons. The Bishops Wars of 1639-40 had been precipitated by King Charles's attempt to impose Anglicanism on the Scottish Kirk, and in February 1641 the Scots called for the abolition of bishops in England as part of their peace terms with the King. A conspicuous opponent of the Crown since the 1620s, by 1640 Pym reasoned that parliament's survival rested on an alliance with the Scottish rebels: if the Scots and the King came to a peace settlement, the King would have no need to maintain a parliament to vote him war funds. Similarly, the Covenanters (those Scots opposed to King Charles's religious policy) had recognised that a strong English parliament was a valuable ally against a hostile Crown. From 1640, Pym and the Covenanters would work together to put political pressure on Charles I. Pym's own desires for church reform probably did not go as far as abolishing bishops (see Russell, 2004) but he nevertheless accepted this proposal, putting his personal views aside to accommodate Covenanter demands.

The Westminster Assembly

In the summer of 1641, Pym introduced legislation to abolish the episcopacy in England. Parliament was unenthusiastic and the bill never went beyond its second reading. Although Pym was more successful with a parliamentary Act to remove altar rails and level the chancels in English churches, the general lack of progress in church reform 'dismayed the Scots'. Pym redoubled his efforts to appease the Covenanters' religious views, and the result was the Westminster Assembly, first convened in July 1643. The Assembly aimed to:

. . . revise the doctrine, liturgy, and government of the English church . . . showed the Presbyterian authorities in Edinburgh that Westminster was serious about church reform, and served as an inducement for the Scots to send an army southward to aid the flagging parliamentary cause (Dixhorn, 2004).

The Scots responded positively and, two months after the Assembly's first session, ratified the Solemn League and Covenant that provided the English parliament with a Scottish military force. Although the Scots made up only one tenth of those who sat on the Assembly they proved 'the most united' religious faction at Wesminster, and among subjects discussed was the observance of religious festivals.

Which brings us to the key date of 1583, because that was the year that the Scottish Kirk, under the direction of the Calvinist reformer John Knox, had prohibited the celebration of Christmas. James I had re-introduced the observance of the nativity in 1618 in an attempt to achieve a religious consensus between his two kingdoms but his action had been declared unlawful by the Glasgow Assembly when Scotland broke from the Crown's authority in 1638 (Pilmot, 1960; Houston, 2008). English puritanism may have forbade Christmas in 1644, but Scottish Presbyterianism got there long before.

. . . revise the doctrine, liturgy, and government of the English church . . . showed the Presbyterian authorities in Edinburgh that Westminster was serious about church reform, and served as an inducement for the Scots to send an army southward to aid the flagging parliamentary cause (Dixhorn, 2004).

The Scots responded positively and, two months after the Assembly's first session, ratified the Solemn League and Covenant that provided the English parliament with a Scottish military force. Although the Scots made up only one tenth of those who sat on the Assembly they proved 'the most united' religious faction at Wesminster, and among subjects discussed was the observance of religious festivals.

Which brings us to the key date of 1583, because that was the year that the Scottish Kirk, under the direction of the Calvinist reformer John Knox, had prohibited the celebration of Christmas. James I had re-introduced the observance of the nativity in 1618 in an attempt to achieve a religious consensus between his two kingdoms but his action had been declared unlawful by the Glasgow Assembly when Scotland broke from the Crown's authority in 1638 (Pilmot, 1960; Houston, 2008). English puritanism may have forbade Christmas in 1644, but Scottish Presbyterianism got there long before.

The influence of Presbyterianism is perhaps seen in Parliament's decision to sit on Christmas Day in 1643. As Dr. Larminie of the History of Parliament Project has shown, this decision was surely motivated by the wish to make a political or religious point, for there seemed to have been no business so urgent as to require Parliamentary scrutiny on that particular day: apart from a brief sitting on the 27th the Commons was able to take the rest of the week off. Importantly, though, they had shown the Covenanters that they were prepared to disregard the traditional Christmas holiday. The following year - when the House enforced the monthly fast at the expense of the traditional feast day - such a show was even more important because by that time a 21,000-strong Covenanter army was fighting for parliament's cause on English soil.

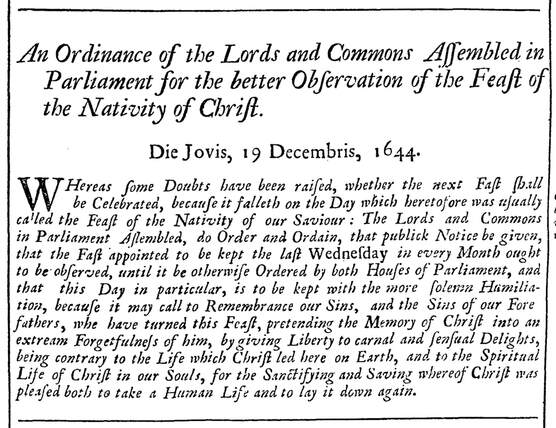

The parliamentary ordinance enforcing the fast on 25 December 1644 stressed that:

The parliamentary ordinance enforcing the fast on 25 December 1644 stressed that:

this Day in particular, is to be kept with the more solemn Humiliation, because it may call to Remembrance our Sins, and the Sins of our Fore fathers, who have turned this Feast, pretending the Memory of Christ into an extreme Forgetfulness of him, by giving Liberty to carnal and sensual Delights, being contrary to the Life which Christ led here upon Earth.

The prohibition of Christmas in 1644, then, was a measure taken by the English parliament to appease their Scottish allies. The importance of this to the Scottish Kirk can be appreciated when we look at that second pivotal date referred to earlier: so tight a grip did the Presbyterian church have on Scotland's popular culture that Christmas Day did not become a public holiday in Scotland until 1958, with Boxing Day only following in 1974. Incidentally, this explains why the Scots place such an emphasis on the New Year celebration of Hogmanay, reserving merry-making for non-religious day.

"Holy-dayes"

Encouraged by the 1644 ordinance, the puritan call to reform the observation of Christmas (so long ignored) increased in volume. This lead to the 1647 “Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals”, which effectively banned the observance of all religious holy days because they were "heretofore superstitiously used and observed". This effectively robbed working people of their days of rest, which had always been afforded them by the annual religious holy days. Acknowledging this, Parliament took care in the 1647 ordinance to ensure that:

all Scholars, Apprentices, and other Servants shall . . . have such convenient reasonable Recreation and Relaxation from their constant and ordinary Labours on every second Tuesday in the moneth throughout the year, as formerly they have used to have on such aforesaid Festivals, commonly called Holy-dayes (Firth & Rait, 1911).

In place of Christmas, Easter and other religious festivals, Parliament granted working people a day's holiday every month. Had this remained in place, the UK population would today enjoy twelve bank holidays a year instead of the eight it now has. How sad that this fact has dropped out of the folk-memory of the Civil War Christmas, supplanted instead by the humourless spectre of Oliver Cromwell confiscating people's mince pies.

all Scholars, Apprentices, and other Servants shall . . . have such convenient reasonable Recreation and Relaxation from their constant and ordinary Labours on every second Tuesday in the moneth throughout the year, as formerly they have used to have on such aforesaid Festivals, commonly called Holy-dayes (Firth & Rait, 1911).

In place of Christmas, Easter and other religious festivals, Parliament granted working people a day's holiday every month. Had this remained in place, the UK population would today enjoy twelve bank holidays a year instead of the eight it now has. How sad that this fact has dropped out of the folk-memory of the Civil War Christmas, supplanted instead by the humourless spectre of Oliver Cromwell confiscating people's mince pies.

Robert Hodkinson

December 2017 (updated 2021)

December 2017 (updated 2021)

Primary sources:

'Acts of the Court of High Commission', in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1634-5, ed. John Bruce (London, 1864), pp. 258-278. British History Online [online] Available: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/chas1/1634-5/pp258-278

(Accessed 01/12/2017).

A Directory for the Public Worship of God Throughout the Three Kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland (Edinburgh: 1645)

Firth, C. H. and Rait, R. S. (eds.) Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660 (London: 1911)

Journal of the House of Commons, vol. 3, 1643-1644 (London, 1802)

Secondary sources:

Dixhoorn, C. 'Westminster Assembly (act. 1643-1652)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004); online edn., May 2009 (Accessed, 10/12/2016).

The Diary of Samuel Pepys [website] Gifford, P. (2019). Available: https://www.pepysdiary.com. (Accessed 01/12/19)

Hayden, R. “Hazzard, Dorothy (d.1674)” in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Houston, R. A. Scotland: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Hutton, R. The Rise and Fall of Merry England: the Ritual Year, 1400-1700. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Larminie, V. "Sitting at Christmas: getting business done, 1643", The History of Parliament (2019)[website] available: https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2019/12/19/sitting-at-christmas-getting-business-done-1643/ (Accessed 18/12/20)

Pimlott, J. A. R., 'Christmas Under the Puritans', in History Today, 10 (December 1960).

Russell, C. 'Pym, John (1584-1643)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004); online edn., May 2009 (Accessed, 10.12.2016).

Reformation History [website] The Reformed Presbyterian Church (2010). Available: http://reformationhistory.org/. (Accessed 09/12/2017)

'Acts of the Court of High Commission', in Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1634-5, ed. John Bruce (London, 1864), pp. 258-278. British History Online [online] Available: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/chas1/1634-5/pp258-278

(Accessed 01/12/2017).

A Directory for the Public Worship of God Throughout the Three Kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland (Edinburgh: 1645)

Firth, C. H. and Rait, R. S. (eds.) Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660 (London: 1911)

Journal of the House of Commons, vol. 3, 1643-1644 (London, 1802)

Secondary sources:

Dixhoorn, C. 'Westminster Assembly (act. 1643-1652)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004); online edn., May 2009 (Accessed, 10/12/2016).

The Diary of Samuel Pepys [website] Gifford, P. (2019). Available: https://www.pepysdiary.com. (Accessed 01/12/19)

Hayden, R. “Hazzard, Dorothy (d.1674)” in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Houston, R. A. Scotland: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Hutton, R. The Rise and Fall of Merry England: the Ritual Year, 1400-1700. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Larminie, V. "Sitting at Christmas: getting business done, 1643", The History of Parliament (2019)[website] available: https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2019/12/19/sitting-at-christmas-getting-business-done-1643/ (Accessed 18/12/20)

Pimlott, J. A. R., 'Christmas Under the Puritans', in History Today, 10 (December 1960).

Russell, C. 'Pym, John (1584-1643)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004); online edn., May 2009 (Accessed, 10.12.2016).

Reformation History [website] The Reformed Presbyterian Church (2010). Available: http://reformationhistory.org/. (Accessed 09/12/2017)