Signing his own Death Warrant:

The 1645 attack on Leicester

and the Trial of King Charles I

and the Trial of King Charles I

Part Three

Leicester and the King's Trial

On 24 January 1649, a Rutland farmer named Humphrey Brown appeared before a committee at Westminster to relate what he could remember of the attack on Leicester that he had witnessed three-and-a-half years before. Brown attested the following: that after surrendering to the Royalists, Parliamentarian soldiers at the Newarke had been robbed, stripped of their clothes and, in many cases, cut and wounded – contrary to the quarter they had been promised. Brown (who had been about eighteen-years-old at the time) claimed that the King himself had done nothing to prevent this maltreatment. Rather, he had encouraged it: “I do not care if they cut them three times more, for they are mine enemies”, Brown claimed to have heard the King say (“or words to that effect”, Brown added). When asked to confirm that the King himself had said this, Brown swore that it had been unmistakably the King, “on horseback, in bright armour, in the said town of Leicester” (Howell, 1107).

The Painted Chamber in The Palace of Westminster (William Capon, 1799), where Humphrey Brown gave evidence to the Court of High Commission in January 1649. Depositions were taken down in this chamber to protect the witnesses from public view in Westminster Hall.

First-hand accounts of those who were injured or suffered loss in the royalist attack survive in Leicester's Borough Hall Papers, recently researched and digitised by the Civil War Petitions project. They make pitiable reading, even 370 years after the event. William Summer, a Leicester tailor, attested that his son had been killed in the fighting and his house plundered, both of which had contributed to his wife's mental collapse: “the fright whereof your petitioner's wife has been distracted ever since”. Katherine Palmer described how her husband Abraham, a weaver, was “totally plundered of all that he had” and imprisoned by the Royalists after the town's surrender, subsequently developing a sickness from which he died. Frances Stevens claimed a widow's pension of four shillings a week for herself and six children after her husband had been killed in the town's defence alongside his officer, Captain Farmer. Robert Holmes, a blacksmith, lost the use of one of his arms. John Hall, a shoe-maker, appealed for charitable relief after being wounded in the town's defence and having “his goods plundered to the very walls”. As the Civil War Petitions website persuasively puts it, bolstering the ranks of the garrison with armed civilians “made the boundary between soldier and civilian a blurred one in the eyes of their assailants” and raises the point that the parliamentarian captives, to whose deliberate wounding the King apparently turned a blind-eye, may have been civilians. Moreover, the plunder of the town following its capture appears to have been well-organised and not merely the result of soldiers running amok. A report that “140 cart loads of the best good and wares in the shops were sent away by Saturday noone towards Newark with a convoy of horse” (A Perfect Relation, 2-3) implies a deliberate and systematic looting of the town. Brown's statement regarding the King was unsupported, but injury clearly had occurred at Leicester and looting appears to have been sanctioned by the royalist command – the ultimate responsibility for which lay with King Charles.

The inclusion of Brown's evidence at the King's trial is something of an oddity. While others testified to witnessing the King's violent action against his subjects at Edgehill, Newbury, etc., they were major engagements that had resulted in far more deaths than had the action at Leicester. The inclusion of Brown's testimony may be explained by a large Leicestershire contingent among the commissioners of the High Court that tried the King, most notably Lord Grey. In December 1648, Grey helped orchestrate the expulsion of moderate voices from the House of Commons that led directly to a vote being carried to put the King on trial. Other Leicestershire men who sat in judgement of the King can be seen to have fallen within Grey's influence: fellow MPs Peter Temple and Thomas Wayte, who had been commissioned as officers by Lord Grey in the first Civil War; James Harrington, MP for Rutland, an area secured by Grey for Parliament in 1643; MP Henry Smith, who was elected to fill the Leicestershire parliamentary seat formerly held by Colonel Theophilus Grey's brother: all of these men put their name and seal to King Charles's death warrant, however reluctant they later claimed to be. Together with Thomas Horton, another Leicestershire army officer, men with close ties to Leicestershire and Rutland made up fifteen percent of the Regicides – surely spurred-on by the leading figure of Lord Grey, who almost certainly pushed for the inclusion of Brown's testament, and the case of Leicester, as evidence against the King.

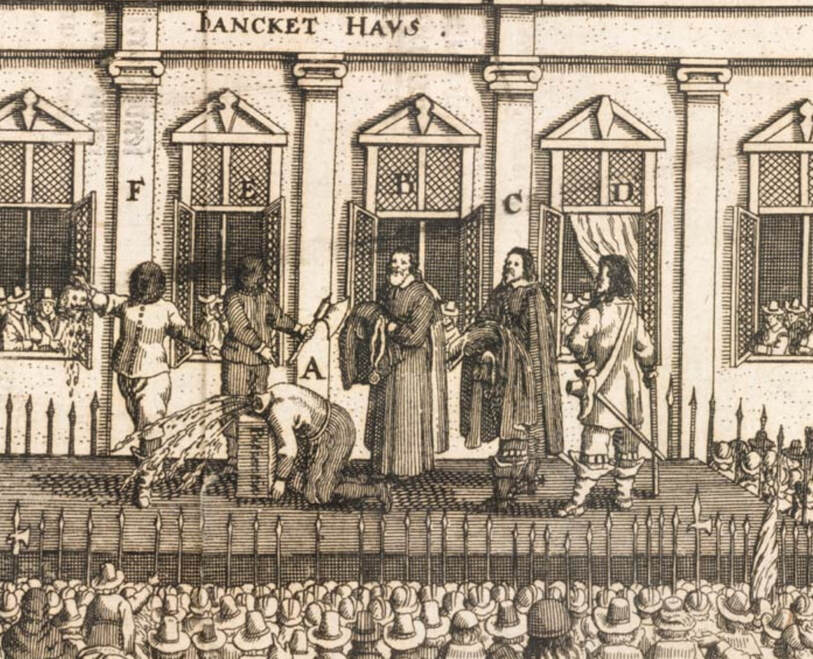

Today, the attack on Leicester may be considered a minor action in the Civil War but surviving evidence shows that it had real significance at the time. Indeed, the spectre of Leicester's sufferings shadowed King Charles to the very end: the officer into whose custody the King was placed during his trial was Francis Hacker. On 30 January 1649 the former garrison commander, captured whilst attempting to escape from Leicester three-and-a-half years before, escorted the King to his place of execution and was present on the scaffold when the axe fell.

Detail of a German engraving of King Charles's execution in Whitehall.

Francis Hacker is shown on the far right of the group, labelled 'D'. (British Museum)

Francis Hacker is shown on the far right of the group, labelled 'D'. (British Museum)

Robert Hodkinson,

May 2021

May 2021

Sources:

- Howell, T. B. A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. 4 (London: 1816)

- “The Petition of William Summer of Leicester, Leicestershire, 1645 to 1647”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/petition/the-petition-of-william-summer-of-leicester-leicestershire-1645-to-1647/. Accessed 28/05/2021

- “The Petition of Katherine Palmer of Leicester, Leicestershire, 1645 to 1647”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/petition/the-petition-of-katherine-palmer-of-leicester-leicestershire-1645-to-1647/. Accessed 28/05/2021

- “The Petition of Frances Steevens and Constance Brewine, both of Leicester, Leicestershire, 1645 to 1647”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/petition/the-petition-of-frances-steevens-and-constance-brewine-of-leicester-leicestershire-1645-to-1647/. Accessed 28/05/2021

- “The Petition of Robert Holmes of Leicester, Leicestershire, 1645 to 1647”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/petition/the-petition-of-robert-holmes-of-leicester-leicestershire-1645-to-1647/. Accessed 28/05/2021

- “The Petition of John Hall of Leicester, Leicestershire, 1646”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/petition/the-second-petition-of-john-hall-1646/.

- Accessed 28/05/2021

- “'Killing a King': The Sack of Leicester and the Trial of Charles I”, Civil War Petitions [website]. Available: https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/blog/killing-a-king-the-sack-of-leicester-and-the-trial-of-charles-i/. Accessed 28/05/2021

- A Perfect Relation of the Taking of Leicester (Thomason E.288[4])

- Barber, S. “Temple, Peter (bap.1599, d. 1663). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004).

- Coward, B. “Hacker, Francis (d.1660), parliamentarian army officer and regicide”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004).

- Gardiner, K. R and Gardiner D. L. “Smith [Smyth], Henry (b. 1619/20, d. in or after 1668)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004).

- Hopper, A. J. “Waite, Thomas (fl.1634-1668), parliamentarian army officer and regicide”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004).

- Kelsey, S. “Harrington, James [formerly Sir James Harrington, third baronet] (bap. 1607, d. 1680)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004).