Charles I's Dream Palace

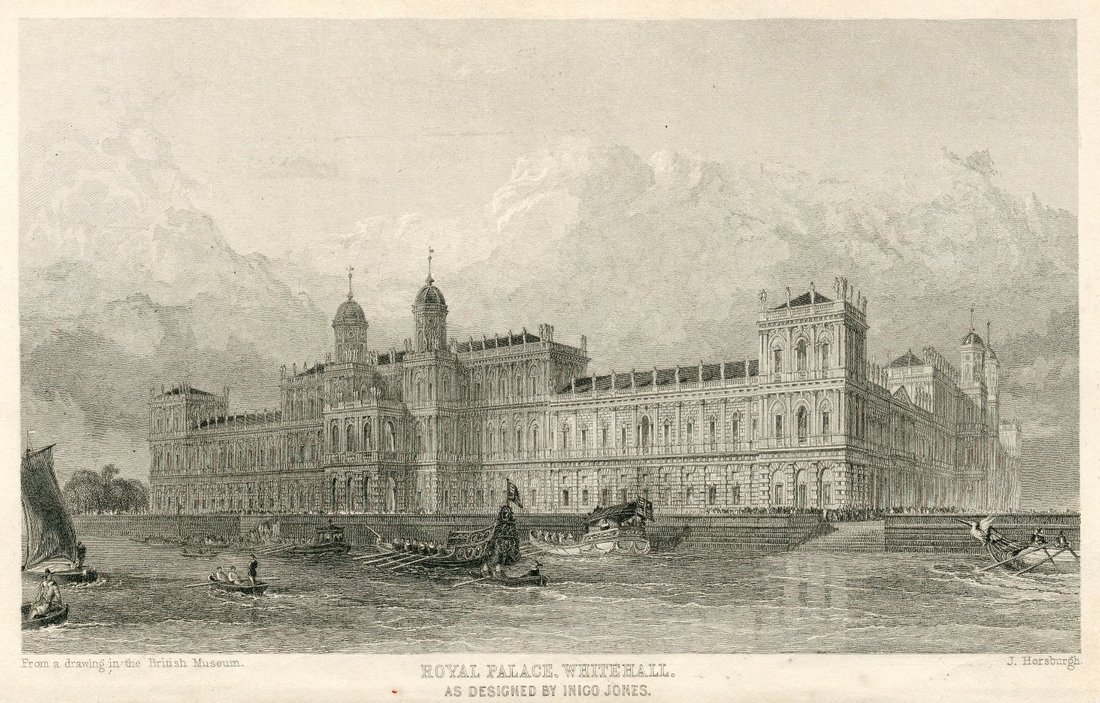

If Charles I and Parliament had agreed on peace terms following the Second Civil War of 1648, there is a good chance that the building in the above engraving would today grace the north bank of the river Thames.

During the autumn of 1648, while Parliament debated how to settle to country's political constitution, the imprisoned Charles I diverted himself by musing on what life would be like once the Civil Wars were behind him. Through the tedious months of his captivity, Charles turned his thoughts to plans of constructing a spectacular royal palace at Whitehall, the largest royal building in Europe at the time.

During the autumn of 1648, while Parliament debated how to settle to country's political constitution, the imprisoned Charles I diverted himself by musing on what life would be like once the Civil Wars were behind him. Through the tedious months of his captivity, Charles turned his thoughts to plans of constructing a spectacular royal palace at Whitehall, the largest royal building in Europe at the time.

By the mid-17th century the Royal residence in London, the old Tudor palace of Whitehall, was a haphazard assortment of buildings clustered round various courts and yards, having been continually expanded over a period of a hundred years to no formal design. The plans for a new Whitehall Palace were intended to sweep away the jumble of crooked roofs and smoking chimneys; in its place would arise a single structure of harmonious and majestic design.

The newest and largest building in the Whitehall Palace complex was the Banqueting House, completed in 1622 and designed by royal architect Inigo Jones. Its neo-classical form (seemingly out of place among the accretion of Tudor brick structures) was to be the hub of Whitehall's redesign. New wings of a similar, classical design were to extend off the Banqueting House and incorporate it into the inner face of a great quadrangle. The new palace was intended to stretch 900 feet along the Thames waterfront and extend back from the river as far St. James' Park. Although its design is often attributed to Jones, it was almost certainly the design of Jones’s pupil, John Webb, copies of whose architectural drawings survive in the collections of Worcester College, Oxford, and the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House.

The newest and largest building in the Whitehall Palace complex was the Banqueting House, completed in 1622 and designed by royal architect Inigo Jones. Its neo-classical form (seemingly out of place among the accretion of Tudor brick structures) was to be the hub of Whitehall's redesign. New wings of a similar, classical design were to extend off the Banqueting House and incorporate it into the inner face of a great quadrangle. The new palace was intended to stretch 900 feet along the Thames waterfront and extend back from the river as far St. James' Park. Although its design is often attributed to Jones, it was almost certainly the design of Jones’s pupil, John Webb, copies of whose architectural drawings survive in the collections of Worcester College, Oxford, and the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House.

The cost of the project was prohibitive: the Banqueting House alone had to £15,000 to build; the new palace called for a construction forty times as large. Neither Charles I nor any future monarch had the financial resources to realise Webb’s design. Webb, and his style of architecture would flourish during the Protectorate and Restoration, though never on the scale of the projected palace.

Yet Webb's design was achieved, albeit only in part and after a hiatus of two hundred and fifty years.

The buildings in Westminster that today accommodate the Treasury were built between 1898 and 1917 to a design by architect John Brydon. Brydon clearly drew on Webb's seventeenth century plan in his design for the new government offices, notably the large circular court and the south towers. An aerial view of present-day Whitehall shows that the Treasury offices today are, more-or-less, one third of Charles I's prospective palace, lifted from Webb's design.

Yet Webb's design was achieved, albeit only in part and after a hiatus of two hundred and fifty years.

The buildings in Westminster that today accommodate the Treasury were built between 1898 and 1917 to a design by architect John Brydon. Brydon clearly drew on Webb's seventeenth century plan in his design for the new government offices, notably the large circular court and the south towers. An aerial view of present-day Whitehall shows that the Treasury offices today are, more-or-less, one third of Charles I's prospective palace, lifted from Webb's design.

It may well be that in his conceiving of a new Whitehall, Charles was thinking optimistically of a not too distant future when his finances would be restored and money granted for such a project by a conciliatory Parliament. Confined to his castle prison on the Isle of Wight, the design may have embodied Charles I's vision of what peace would look like. Viewing the approved design of the new palace three hundred years on, it is hard to dismiss the idea that such grandiose architecture carried a political weight. As with all palaces, its scale and opulence was intended as much to miniaturise the ordinary subject as impress visiting dignitaries. The symmetry of its classical proportions was intended to reflect a kingdom rebalanced after political turmoil, once the monarch restored to his proper place.

Prisoner that he was, it is difficult to consider Charles I’s approval of Webb’s design as anything other than delusional. It is true that a compliant Parliament had reopened peace negotiations in September 1648, but by the time Parliament voted on 5 December to accept the Treaty of Newport as basis of peace the army already had Charles I in its custody: Whitehall’s Banqueting House, rather than providing the template for a new, neo-classical palace, would instead provide the backdrop to Charles I’s public execution.

Robert Hodkinson

January, 2017

Sources:

Banister, F. A History of Architecture in the Comparative Method (6th edn) (New York: Scribers, 1921).

Braddick, M.‘God’s Fury, England’s Fire’: A New History of the English Civil Wars (London: Penguin, 2008).

Government Art Collection [online] available: http://www.gac.culture.gov.uk. accessed 14.01.17.

'The Treasury Building, 1 Horse Guards Road' [online]

available: https://www.gov.uk/government/history/1-horse-guards-road. accessed 14.01.17

Prisoner that he was, it is difficult to consider Charles I’s approval of Webb’s design as anything other than delusional. It is true that a compliant Parliament had reopened peace negotiations in September 1648, but by the time Parliament voted on 5 December to accept the Treaty of Newport as basis of peace the army already had Charles I in its custody: Whitehall’s Banqueting House, rather than providing the template for a new, neo-classical palace, would instead provide the backdrop to Charles I’s public execution.

Robert Hodkinson

January, 2017

Sources:

Banister, F. A History of Architecture in the Comparative Method (6th edn) (New York: Scribers, 1921).

Braddick, M.‘God’s Fury, England’s Fire’: A New History of the English Civil Wars (London: Penguin, 2008).

Government Art Collection [online] available: http://www.gac.culture.gov.uk. accessed 14.01.17.

'The Treasury Building, 1 Horse Guards Road' [online]

available: https://www.gov.uk/government/history/1-horse-guards-road. accessed 14.01.17