Humpty Dumpty Exploded: de-constructing a Civil War Myth

Living-history thrives on colourful anecdote. Nothing can be guaranteed to capture the public's interest more than a quirky fact or a gory aspect of 17th Century life. Witch trials and barber-surgeons are always good entertainment, likewise the tale of Verney's severed hand, still clutching the Royal standard when it was seized at Edgehill. But some Civil War stories are embellished in the re-telling to the point where they begin to take on a life of their own. Humpty-Dumpty is a case in point.

As many readers will already know, 'Humpty-Dumpty' is said to be the name of a Royalist cannon employed at the siege of Colchester in the Second Civil War of 1648. When Colchester was surrounded by Fairfax's army, 'Humpty' was brought into action and lifted into the belfry of St. Mary's church to provide the gunners with a good field of fire over the town walls. Sadly, the gun's recoil proved too strong for the church's medieval timbers, causing the tower to collapse and taking Humpty and its gunners with it. The episode was immortalised in the lines of the nursery rhyme: 'All the King's horses and all the King's men, / Couldn't put Humpty together again.'

Yet none of this is true.

Yet none of this is true.

St. Mary-at-the-Walls, Colchester. Church tower showing 18th century restoration following damage in the Civil War.[www.interestingincolchester.com]

St. Mary-at-the-Walls, Colchester. Church tower showing 18th century restoration following damage in the Civil War.[www.interestingincolchester.com] A church did collapse during the siege of Colchester, and the royalists did lose the gun that had been placed in its steeple. The event was described in detail by the Colchester clergyman and historian, Reverend Philip Morant. According to Morant, the Royalists had established a battery at “St. Maries-fort and Steeple”, and in the steeple itself, “a platform was made in a frame in the bells, and a brass saker planted, which, flanking their [the Parliamentarians] trench, did them much injury”. As for the tower's collapse, Morant describes this as having been caused by returning fire from Parliamentarian guns which, “beat down one side of it in a short time, with a great part of the church, breaking the saker that was planted there . . . the gunner, and one of the matrosses, were killed.” (Cromwell, p.181).

The steeple was not rebuilt until 1713.

The steeple was not rebuilt until 1713.

Morant was writing in the mid-eighteenth century. His information about the siege may well have been gleaned from the folk-memory of Colchester inhabitants, but the fact that he was not there at the time must cast some doubt on the veracity of his account. Nevertheless, the divergence of Morant's version of events from that which is told today is telling. Notably absent is any mention of the name 'Humpty Dumpty'. When, then, was the connection made between the nursery rhyme and the 1648 siege?

The rhyme itself is not attested in English until c.1800 and the lines concerning 'All the King's horses' are even later, not documented until 1833 (Oxford English Dictionary). Moreover, the rhyme's origins are believed to be French. Nothing to do with the English Civil War at all, it would seem. In fact, the Colchester connection with Humpty Dumpty appears to have been made very recently, perhaps as little forty years ago. In 1994 the compilers of The Victoria County History of Essex were forced to conclude that “There appears to be no evidence to support the suggestion, popularized c.1980, that another nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty, derives from the destruction of a cannon at the siege of Colchester in 1648.” (Baggs, et al., p.1).

There appears to have been no link made between the nursery rhyme and the Civil War until as recently as 1956, when Oxford professor, David Daub, made the suggestion that Humpty Dumpty was the name given to a siege engine employed by the Royalists during their siege of Gloucester in 1643.

The rhyme itself is not attested in English until c.1800 and the lines concerning 'All the King's horses' are even later, not documented until 1833 (Oxford English Dictionary). Moreover, the rhyme's origins are believed to be French. Nothing to do with the English Civil War at all, it would seem. In fact, the Colchester connection with Humpty Dumpty appears to have been made very recently, perhaps as little forty years ago. In 1994 the compilers of The Victoria County History of Essex were forced to conclude that “There appears to be no evidence to support the suggestion, popularized c.1980, that another nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty, derives from the destruction of a cannon at the siege of Colchester in 1648.” (Baggs, et al., p.1).

There appears to have been no link made between the nursery rhyme and the Civil War until as recently as 1956, when Oxford professor, David Daub, made the suggestion that Humpty Dumpty was the name given to a siege engine employed by the Royalists during their siege of Gloucester in 1643.

Humpty Dumpty Goes to Gloucester

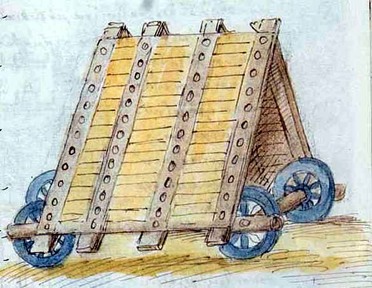

Daub's proposal was based on contemporary accounts of the Gloucester siege, although, as with Morant, the name Humpty Dumpty is never mentioned. The description of the siege engines is as follows:

The King's Forces, by the Directions of Dr. Chillingworth, had provided certain Engines, after the manner of the Roman Testudines cum Pluteis, wherewith they intended to Assault the City between the South and West Gates; They ran upon Cart-Wheels, with a Blind of Planks Musquet-proof, and holes for four Musqueteers to play out of, placed upon the Axle-tree to defend the Musqueteers and those that thrust it forwards, and carrying a Bridge before it; the Wheels were to fall into the Ditch, and the end of the Bridge to rest upon the Towns Breast-works, so making several compleat Bridges to enter the City. To prevent which, the Besieged intended to have made another Ditch out of their Works, so that the Wheels falling therein, the Bridge would have fallen too short of their Breast-works into their wet More, and so frustrated that Design.

From the wording it would seem that these engines were never put into action, though they were certainly built, and reported to have been captured following the raising of the siege and drawn into Gloucester, perhaps in the manner of a trophy (Fosbrooke, p.78). As the siege of the city was raised before the engines could be deployed there was little possibility of them suffering a 'fall' (into a deep entrenchment, say) and being irreparably damaged, which the nursery rhyme's narrative demands.

Professor Daube's theory (and it should be noted that he was Regius Professor of Civil Law at Oxford, not a historian) was inspired solely by idea that the solid rhythm of the rhyme suggested to him that Humpty Dumpty was something more solid than an egg (Young, pp.90-91). A recent study of the subject has dismissed Daube's theory as a fanciful spoof, alleging that the author might have derived “some satisfaction if, as with the current craze for horrific 'urban legends', he can watch his story spreading to a public gullible enough to repeat it in earnest” (Hunt, vol.1, p.277). Daube's theory certainly gained currency, featuring in the plot of a childrens opera based around the siege of Gloucester, All the King's Men, staged in 1969. In all probability, the circulation of the Daube's theory supplied the inspiration for Colchester's claim for the origin of the Humpty Dumpty rhyme, which had been made by 1980.

"Mr. Punch"

With no reference to the name Humpty Dumpty in the accounts of either Colchester's siege or that of Gloucester, and the probability that Daube's theory was merely a tongue-in-cheek flight of fancy, is there a Civil War connection with the nursery rhyme at all? Interestingly enough, the siege of Gloucester also witnessed the destruction of a large, Royalist gun. This was said to be “their biggest mortar piece”, as a Parliamentarian account described it, which “brake at the first discharging of it; they say the biggest in England.” (Fosbrooke, p.71) Even so, this is as an unlikely a candidate for being 'the real' Humpty Dumpty as either of the two theories aforementioned. It is true that short-barrelled guns, such as a mortar pieces, were given amusing and fitting names, and a good example is that recorded by Samuel Pepys. In 1669, the diarist was present at London's Artillery Ground to watch the demonstration of newly-cast gun, which was named Punchinello due to its “bigness and shortness” (Pepys, 20 April 1669). Not long after, Pepys was amused to overhear a married couple referring to their child as 'Punch': “that word being become a word of common use”, Pepys noted, “for all that is thick and short.” (Pepys, 30 April 1659) No Humpty Dumpty here either, then, 'Mr. Punch' being the more likely name for a mortar-piece or similar field gun.

The 'Real' Humpty Dumpty

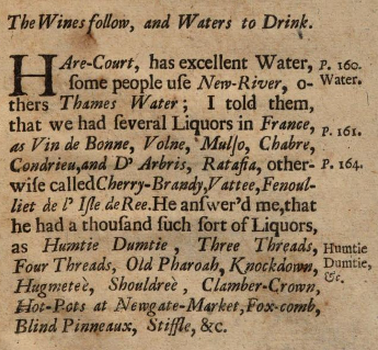

Humpty Dumpty was in fact neither a cannon nor a siege engine. He was a drink. A dictionary of slang published c.1690 defines 'Humptey-Dumptey' as a name for “Ale boild with Brandy”. In a guide to London written by a Frenchman, Sorbier, and published in English at round the same date, “Humtie Dumtie” appears in a list of beverages available to purchase in the capital. Its name would seem to be a variant of 'hum', a common name in this period for strong beer. Etymology has yet to find a link between the name of this 17th century brew and the later use of the phrase 'humpty dumpty' in reference to a small, squat body – which is clearly the term's use if describing the shape of a cumbersome siege engine or a mortar-piece. Despite the similarity in sound with words such as 'dumpy' and 'humped', this was not the phrase's application in the 17th century (Pepys's 'punchinello' being the more obvious slang term for something thick and short in appearance). The Oxford English Dictionary cites the use of 'humpty-dumpty' to describe 'a short or clumsy person of either sex' as no earlier than 1785.

The 'Humpty Dumpty' personification, then, would appear to be a late 18th century coinage. The name does not appear in accounts of English Civil War. Indeed, the very idea of a connection between Humpty Dumpty and the Civil War was not made until 1956.

The short time in which such an apparent fabrication can gain acceptance as a fact should serve as a caveat to any re-enactor who educates the public with anecdotes masquerading as truths. It is neither education nor 'edutainment', it is simply untrue. The Civil War's Humpty Dumpty is no more a historical fact that the story of an egg-man falling off a wall.

Robert Hodkinson

April, 2016

Sources:

Baggs, A. P. et al., 'The Borough of Colchester', in A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9, the Borough of Colchester, ed. Janet Cooper and C R Elrington (London, Victoria County History, 1994).

'B. E.' A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew (London: Hawes, et al. c.1690).

Cromwell, T. History and Description of the Ancient Town and Borough of Colchester in Essex (London, Youngman, 1826).

Fosbrooke, T. D. An Original History of the City of Gloucester (London: Nichols & Son, 1819).

Goss, A. 'Humpty Dumpty – Fact or Fiction', interestingincolchester.co.uk [online] available: https://www.interestingincolchester.co.uk/humpty-dumpty/ accessed: 16.04.2017.

Hunt, P. International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (vol.1) (Abingdon: Routledge, 2001).

MS Hunter 220 (U.2.11) University of Glasgow Library Special Collections Department [online]. available: http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/aug2008.html accessed 16.04.2017.

King, W. A Journey to London in the Year 1698 (London: Baldwin, 1699).

Oxford English Dictionary [online]. available: www.oed.com accessed 16.04.2017.

Pepys, S. Diary [online]. available: http://www.pepysdiary.com accessed 16.04.2017.

Rushworth, J., 'Historical Collections: Military action in 1643', in Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 5, 1642-45 (London: Browne,1721), pp. 263-309. British History Online [online]. available http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol5/pp263-309. accessed 16.04.2017.

Young, Peter Tortoise (London: Reaktion, 2003).

The short time in which such an apparent fabrication can gain acceptance as a fact should serve as a caveat to any re-enactor who educates the public with anecdotes masquerading as truths. It is neither education nor 'edutainment', it is simply untrue. The Civil War's Humpty Dumpty is no more a historical fact that the story of an egg-man falling off a wall.

Robert Hodkinson

April, 2016

Sources:

Baggs, A. P. et al., 'The Borough of Colchester', in A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9, the Borough of Colchester, ed. Janet Cooper and C R Elrington (London, Victoria County History, 1994).

'B. E.' A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew (London: Hawes, et al. c.1690).

Cromwell, T. History and Description of the Ancient Town and Borough of Colchester in Essex (London, Youngman, 1826).

Fosbrooke, T. D. An Original History of the City of Gloucester (London: Nichols & Son, 1819).

Goss, A. 'Humpty Dumpty – Fact or Fiction', interestingincolchester.co.uk [online] available: https://www.interestingincolchester.co.uk/humpty-dumpty/ accessed: 16.04.2017.

Hunt, P. International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (vol.1) (Abingdon: Routledge, 2001).

MS Hunter 220 (U.2.11) University of Glasgow Library Special Collections Department [online]. available: http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/aug2008.html accessed 16.04.2017.

King, W. A Journey to London in the Year 1698 (London: Baldwin, 1699).

Oxford English Dictionary [online]. available: www.oed.com accessed 16.04.2017.

Pepys, S. Diary [online]. available: http://www.pepysdiary.com accessed 16.04.2017.

Rushworth, J., 'Historical Collections: Military action in 1643', in Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 5, 1642-45 (London: Browne,1721), pp. 263-309. British History Online [online]. available http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol5/pp263-309. accessed 16.04.2017.

Young, Peter Tortoise (London: Reaktion, 2003).